A Metamorfose dos Pássaros (The Metamorphosis of Birds, 2020) by Catarina Vasconcelos

Catarina Vasconcelos is a painter of the shot and a seamstress of the raccord. Choose a random frame from her last film: you will have the first half of the previous sentence justified; choose a random cut: you will have the second. In Vasconcelos’ film, there is no image that you don’t want to stop to appreciate its singular beauty, just as there is no cut that you don’t want to rewind to study the skillful connection between one shot and the next. The result of patient hands and bustling creativity, The Metamorphosis of Birds is, in sum, the work of a genuine artisan of the cinema.

Yes, I’m also referring to those shots of pictorial influences (created in collaboration with DP Paulo Menezes), both the tableaux vivants with the supposed Vasconcelos’ family and the still lifes that, at first, seem inspired by some unknown Chardin painting. It’s not hard to believe that she comes from Visual Arts, as the film demonstrates a meticulous sensitivity to color, texture, and composition. But the most captivating are those sonic (a child’s light breath leads to a resounding gale) and visual raccords (a woman’s watery eye leads to the one of a seahorse), a game full of sonic and graphic relations where Vasconcelos appears to put the world in permanent communication: people with places, humans with animals, a family with a country’s History.

And with this need to connect an intimate universe with a broader one, Vasconcelos writes a long visual sonnet. Through it, she emphasizes the importance of the maternal figure, her human symbol of strength, courage, and resilience, and where its irreversible loss leads to a profound change in the family structure and dynamics.

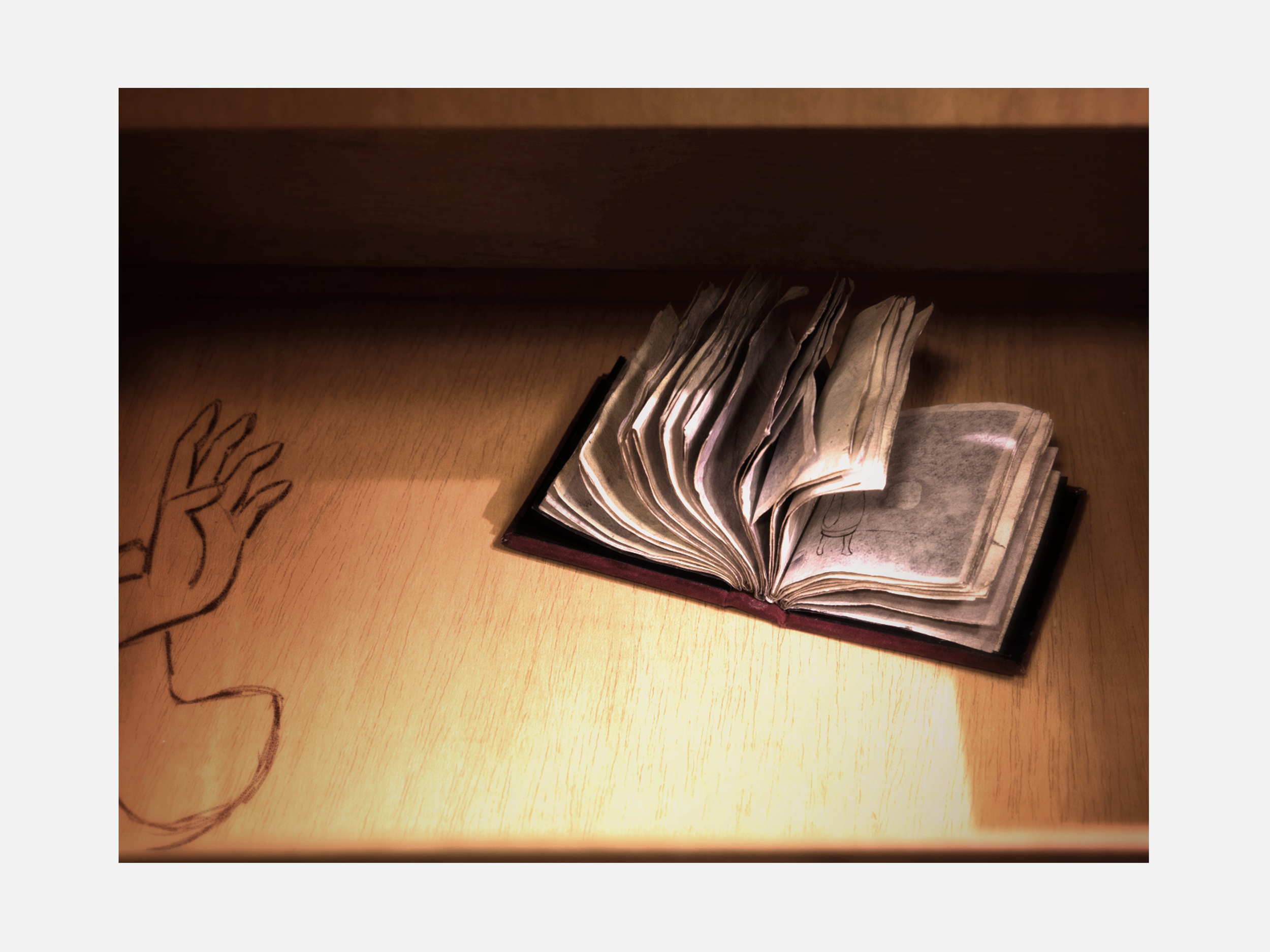

Therefore, it is also a film about grief and its processing. But, at the same time, Vasconcelos seems to believe in something like the remains of persons in objects that belonged to them, such is the use of so much daily memorabilia: sofas, pillows, mirrors, books, stamps and even a fossil, inanimate witnesses to the (possible) domestic events that the filmmaker immortalizes. It is as if Vasconcelos transcribed a letter recited by all those artifacts, sets and props, deciding to respond to them through images, sounds and her fertile imagination. Hence, the poetic liberties she pursues are never seen as adulterations, but as part of the brick and mortar required to build an emotionally honest monument to her family. It is left to be said that this film is, of course, held on the feeling of “saudade” and on the inexecutable desire for temporal retrocession that characterizes it.

Regarding this, three moments occur to me in particular, all of them with trees—women in Vasconcelos’ family are compared to them for their symbolic verticality and for how they serve as shelters for “the birds”, that is, the children. The first, the one in which Vasconcelos, by using the reverse motion effect, restores leaves to the branches from which they were torn; the second, the one in which she tries to push up a felled tree, as if trying to reinstate its lost verticality (a metaphor for the impossibility of returning the maternal entity to life); and the third, the one where, in a wood, she points a mirror to the trees that are “backwards”, that is, in the past. Because it is between the past and present that the film wanders, just as it wanders between documentary and fiction, between fact and poetry, between presence and absence, between life and death, between man and woman, between land and sea. And among all these wanderings, only one word permanently resonates: “mother”.

— Duarte Mata